Bail Bonds

Every year, we spend over $100 billion to keep 2.2 million people incarcerated. Many criminals belong behind bars. But too many others, especially nonviolent drug offenders, are serving unnecessarily long sentences.

Bail exists because of the most fundamental idea of our criminal justice system: Defendants are presumed innocent until proven guilty.

The Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that “excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel or unusual punishment inflicted.” A natural result of this right is the constitutional guarantee of reasonable bail pending trial, a concept that has been universally affirmed by the Courts of this great Union.

On July 17th 2017, a judge in Chicago ruled that courts there could no longer hold people in jail on bail simply because they could not afford it. This is the latest in a series of judicial and legislative actions designed to reform the cash bail system that has come under increasing scrutiny in the wake of abusive court practices uncovered in Ferguson, MO and following the death of Kalief Browder in New York City.

Ferguson was just one of many cities that has been found to use cash bail to pressure defendants into agreeing to plea deals rather than taking their cases to court. Defendants often spent several days in jail on cases where incarceration for an actual conviction was highly unlikely. According to an investigation by The Atlantic, almost two-thirds of people in local jails are awaiting trial, and a full 90% of them are there because they cannot afford bail.

In the case of Kalief Browder, the results turned out to be fatal. Browder was held for three years based on an unsupported accusation that he stole a backpack. He spent two of those years in solitary confinement as a juvenile. After years of trying to pressure him into a plea deal, the Bronx DA’s office admitted that they had no case. Shortly after his release he killed himself, having never recovered from the traumas of his abuse in jail.

FACT: as 100,000 people are held in solitary confinement in federal, state and local jurisdictions, and said the practice — especially for juveniles and people with mental illness — has the “potential to lead to devastating, lasting psychological consequences

The Bail Bond industry works through bonds that usually cost defendants 10 percent of the bail amount (mostly non-recoverable) in local cases and 15% for a federal bail bond— whether or not they show up in court. A bail bonding agency, acting for the defendant, will arrange with the court to have a suspect released from jail pending the trial in exchange for money or collateral, which may be cash, assets, or a bond. In many cases this means that poor people either languish in jail in conditions that make them more likely to accept unfavorable or even false plea deals, or pay significant fees, based on their average income of less than $16,000, to bail bond companies.

According to the Bail Yes website, new bail bondsmen can expect to earn about $25,000 annually. Bail bondsman Greg Rynerson says that newly licensed bail bond agents working for a company make from $10 to $15 hourly.

The FAU supports bail reform as a central element of any program to reduce incarceration rates, especially in local jails. It also represents a basic social justice issue as the burdens of the current system rest overwhelmingly on the poor.

FAU supports laws designed to ensure that criminal defendants would be detained or released from jail pending trial based on individual risk factors of danger to the community or flight, and not their ability to pay a monetary bond.

We will work to create a program whereas defendants are instead subjected to intensive community supervision. Currently our demostration cities will be Cincinnati and San Diego.

At the same time, we at FAU are realists and know that cash used to secure appearances in court – if the defendant doesn’t have a reason to appear (and money is a great motivator), study after study shows that they don’t bother showing up.

Furthermore, we do not support laws that encourage re-arrested on a “bond violation” as a non violent criminal that supports just another “non violent” charge….and they’re released again, with no motivation to show up again. In cases like that cash or its equivalent must be in place.

We understand that these reforms are not going to go unchallenged by the commercial bail bond industry which makes millions every year loaning money to people to cover their bail. Nationally, the bail bond industry has been mobilizing. At the local level, bail bond companies have been pouring cash into legislative and DA races to try to block or at least temper reforms that would reduce their role.

FAU will implement a program that will gather allies to create a national alliance with FAU state associations to advanced People of African Descent in the Bail Bond Industry profession through legislative advocacy, professional networking, continuing education, support of bail agent certification, liability insurance and development of a code of ethics. We start in Ohio and California.

_____________________________________________________________________________

History of Bail Bonds

In medieval England, the sheriffs originally possessed sovereign authority to release or hold suspected criminals. Some sheriffs would exploit the bail for their own gain. The Statute of Westminster (1275) limited the discretion of sheriffs with respect to the bail. Although sheriffs still had the authority to fix the amount of bail required, the statute stipulates which crimes are bailable and which ones are not.

In the early 17th century, King Charles I ordered noblemen to issue him loans. Those who refused were imprisoned. Five of the prisoners filed a habeas corpus petition arguing that they should not be held indefinitely without trial or bail. In the Petition of Right (1628) the Parliament argued that the King had flouted the Magna Carta by imprisoning people without just cause.

The Habeas Corpus Act (1679) states, “A Magistrate shall discharge prisoners from their Imprisonment taking their Recognizance, with one or more Surety or Sureties, in any Sum according to the Magistrate’s discretion, unless it shall appear that the Party is committed for such Matter or offenses for which by law the Prisoner is not bailable.”

The English Bill of Rights (1689) states that “excessive bail hath been required of persons committed in criminal cases, to elude the benefit of the laws made for the liberty of the subjects. Excessive bail ought not to be required.” This was a precursor of the Eighth Amendment to the US Constitution.

Bail law in the United States

In pre-independence America, bail law was based on English law. Some of the colonies simply guaranteed their subjects the protections of British law. In 1776, after the Declaration of Independence, those which had not already done so enacted their own versions of bail law.

Section 9 of Virginia’s 1776 Constitution states “excessive bail ought not to be required…” In 1785, the following was added, “Those shall be let to bail who are apprehended for any crime not punishable in life or limb…But if a crime be punishable by life or limb, or if it be manslaughter and there be good cause to believe the party guilty thereof, he shall not be admitted to bail.”

Section 29 of the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776 states “Excessive bail shall not be exacted for bailable offenses”.

The Eighth Amendment in the US Federal Bill of Rights is derived from the Virginia Constitution (then a slave state), “Excessive bail shall not be required…”, in regard to which Samuel Livermore commented, “The clause seems to have no meaning to it, I do not think it necessary. What is meant by the term excessive bail…?!” The Supreme Court has never decided whether the constitutional prohibition on excessive bail applies to the States through the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Sixth Amendment, to the Constitution, like the English Habeas Corpus Act of 1678, requires that a suspect must “be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation” and thus enabling a suspect to demand bail if accused of a bailable offense.

The Judiciary Act of 1789

In 1789, the same year that the Bill of Rights was introduced, Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1789. This specified which types of crimes were bailable and set bounds on a judge’s discretion in setting bail. The Act states that all non-capital crimes are bailable and that in capital cases the decision to detain a suspect, prior to trial, was to be left to the judge.

The Judiciary Act states, “Upon all arrests in criminal cases, bail shall be admitted, except where punishment may be by death, in which cases it shall not be admitted but by the supreme or a circuit court, or by a justice of the supreme court, or a judge of a district court, who shall exercise their discretion therein.”

We believe that the Modern Bail Bonds Industry got its start in 1850

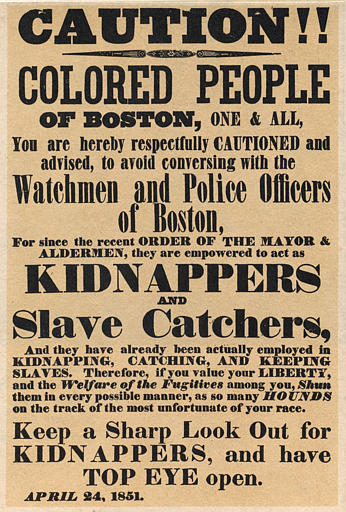

The Fugitive Slave Law or Fugitive Slave Act was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern slave-holding interests and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was an Act of the United States

Congress to give effect to the Fugitive Slave Clause of the U.S. Constitution (Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3 Note: This was superseded by the Thirteenth Amendment ieSection 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. ) which guaranteed a right of a slaveholder to recover an escaped slave. The Act’s title was “An Act respecting fugitives from justice, and persons escaping from the service of their masters” and created the legal mechanism by which that could be accomplished.

The Act was one of the most controversial elements of the 1850 compromise and heightened Northern fears of a “slave power conspiracy”. It required that all escaped slaves were, upon capture, to be returned to their masters and that officials and citizens of free states had to cooperate in this law. Abolitionists nicknamed it the “Bloodhound Law” for the dogs that were used to track down runaway slaves

The Bail Reform Act of 1966

In 1966, Congress enacted the Bail Reform Act of 1966 which states that a non-capital defendant is to be released, pending trial, on his personal recognizance or on personal bond, unless the judicial officer determines that such incentives will not adequately assure his appearance at trial. In that case, the judge must select an alternative from a list of conditions, such as restrictions on travel. Individuals charged with a capital crime, or who have been convicted and are awaiting sentencing or appeal, are to be released unless the judicial officer has reason to believe that no conditions will reasonably assure that the person will not flee or pose a danger. In non-capital cases, the Act does not permit a judge to consider a suspect’s danger to the community, only in capital cases or after conviction is the judge authorized to do so.

The 1966 Act was particularly criticized within the District of Columbia, where all crimes formerly fell under Federal bail law. In a number of instances, persons accused of violent crimes committed additional crimes when released on their personal recognizance. These individuals were often released yet again.

The Judicial Council committee recommended that, even in non-capital cases, a person’s dangerousness should be considered in determining conditions for release. The District of Columbia Court Reform and Criminal Procedure Act of 1970 allowed judges to consider dangerousness and risk of flight when setting bail in noncapital cases.

Current U.S. bail law

In 1984 Congress replaced the Bail Reform Act of 1966 with new bail law, codified at United States Code, Title 18, Sections 3141 – 3150. The main innovation of the new law is that it allows pre-trial detention of individuals based upon their danger to the community; under prior law and traditional bail statutes in the U.S., pre-trial detention was to be based solely upon the risk of flight.

18 USC 3142(f) provides that only persons who fit into certain categories are subject to detention without bail: persons charged with a crime of violence, an offense for which the maximum sentence is life imprisonment or death, certain drug offenses for which the maximum offense is greater than 10 years, repeat felony offenders, or if the defendant poses a serious risk of flight, obstruction of justice, or witness tampering. There is a special hearing held to determine whether the defendant fits within these categories; anyone not within them must be admitted to bail.