The First Black Expo

The first black expo geared toward African-Americans was held in 1895 in Atlanta to help further educate Americans on African-American accomplishments. Even though many African-Americans (freed and otherwise) were already credited with numerous inventions and technological advancements which helped to modernize this country, during the years of slavery and for the three decades following emancipation, expositions were held which excluded African-Americans and their products and services.

Background

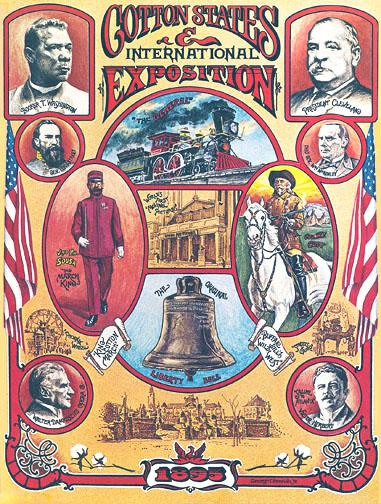

In 1887, Charles A. Collier a capitalist, banker was also the President of the Piedmont Exposition which bought 189 acres (0.76 km2) of land to form Piedmont Park and the Gentleman’s Driving Club. In just 104 days, Collier and the rest of the Company managed to build the structures and prepare the grounds for the Piedmont Exposition held at the newly named Piedmont Park. Many prominent figures of the day were in attendance to see the displays. Governor David B. Hill of New York spoke at the event as well as President Grover Cleveland who attended with his new wife, Frances Folsom, on October 19. The event closed on October 22 with a total attendance of about 200,000. The Exposition was also a chance for Atlanta to prove that it was ready to host the World’s Fair (also known as Cotton States and International Exposition).

Afterward, Collier was named President of the Cotton States and International Exposition Company charged with planning the 1895 World’s Fair which at the time was known as the Cotton States and International Exposition. It was where Alexander Graham Bell introduced the telephone, the Ferris wheel made its debut, the diesel engine stole the show, Welch’s Grape Juice became a national hit, and Aunt Jemima could be seen in the flesh.

The First Black Expo

On October 16, 1894, Charles A. Collier and lawyer and future Atlanta Mayor and John Randolph Lewis. who during the Civil War was made a Union Brevet Brigadier General, wrote to Booker T. Washington making him the Chief Commissioner of the State of Alabama for the Exposition and charging him with creating an exhibit show casing the talents of African-Americans in Alabama.

During that year Booker T. Washington, Bishop W. J. Gaines of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the 1890 author of “African Methodism in the South; or Twenty-Five Years of Freedom” along with other highly respected citizens of Atlanta came together to discuss the inclusion of African-Americans in the Cotton States and International Exposition. They believed that the participation of African-Americans would show that the two races (Black and Caucasian) shared common interests and concerns. African-Americans were invited to create exhibits that highlighted their achievements since the end of slavery.

During that year Booker T. Washington, Bishop W. J. Gaines of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the 1890 author of “African Methodism in the South; or Twenty-Five Years of Freedom” along with other highly respected citizens of Atlanta came together to discuss the inclusion of African-Americans in the Cotton States and International Exposition. They believed that the participation of African-Americans would show that the two races (Black and Caucasian) shared common interests and concerns. African-Americans were invited to create exhibits that highlighted their achievements since the end of slavery.

At dawn on September 18, 1895, the city of Atlanta stirred and at six a.m. brought the moment everyone had been waiting for: at last, the gates of the Cotton States and International Exposition were thrown ajar.. It would be open from September 18 to December 31, 1895

The Cotton States Exposition’s goals were to foster trade between southern states and South American nations as

well as to show the products and facilities of the region to the rest of the nation and Europe. Over the three

months of the Exposition, over 800,000 attendees visited the event. There were exhibits by six states and special

buildings featuring the accomplishments of women and blacks.

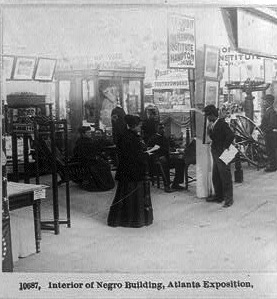

The “Negro Building” included approximately 30,000 square feet.

Freed men across the nation were allowed to use “the Negro Building”—a 30,000 square foot (112 feet wide and 270 feet and 70 feet high) structure – to show their wares. African-Americans filled the building, producing their own exhibits and raising all necessary funds as evidence of their self-sufficiency and a show of their interest.

Freed men across the nation were allowed to use “the Negro Building”—a 30,000 square foot (112 feet wide and 270 feet and 70 feet high) structure – to show their wares. African-Americans filled the building, producing their own exhibits and raising all necessary funds as evidence of their self-sufficiency and a show of their interest.

The building and exhibit were managed by a group of prominent African-American men. This “Central Board,” which met at Clark University, included such influentials as political leader and educator Booker T. Washington and other African-American men of distinction from across the nation.

Home of the Booker T. Washington “Atlanta Compromise” Speech

Many speculate this was allowed becuase on opening day September 18, 1895, the African American educator and leader Booker T. Washington delivered his famous “Atlanta Compromise” speech at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta. The speech laid the foundation for the Atlanta compromise, an agreement between African-American leaders and Southern white leaders in which Southern blacks would work meekly and submit to white political rule, while Southern whites guaranteed that blacks would receive basic education and due process of law. The term “Atlanta Compromise” was given to the speech by W.E.B Dubois, who believed it was insufficiently committed to the pursuit of social and political equality for blacks.

Two years earlier, Washington had spoken in Atlanta during the international meeting of Christian Workers. That audience, comprising northern and southern whites, responded favorably to his speech, in which he advocated vocational-industrial education for blacks as a means of improving southern race relations. In the spring of 1895 Washington traveled to Washington, D.C., with a delegation of mostly white Georgians to solicit support from Congress for an exposition on social and economic advances in the South. Washington pointed out to a congressional committee that since emancipation, blacks and whites had made advancements in race relations that should be highlighted in an exposition, and he urged federal support for the event, to be held in Atlanta. This speech, along with his 1893 address to the Christian Workers, prompted the exposition’s board of directors to ask Washington to speak at its opening exercises.

Washington’s speech responded to the “Negro problem”—the question of what to do about the abysmal social and economic conditions of blacks and the relationship between blacks and whites in the economically shifting South.

Washington began with a call to the blacks, who composed one third of the Southern population, to join the world of work. He declared that the South was where blacks were given their chance, as opposed to the North, especially in the worlds of commerce and industry. He told the white audience that rather than relying on the immigrant population arriving at the rate of a million people a year, they should hire some of the nation’s eight million blacks. He praised blacks’ loyalty, fidelity and love in service to the white population, but warned that they could be a great burden on society if oppression continued, stating that the progress of the South was inherently tied to the treatment of blacks and protection of their liberties.

The speech appealed to white southerners, in that Washington promised his audience that he would encourage blacks to become proficient in agriculture, mechanics, commerce, and domestic service, and to encourage them to “dignify and glorify common labour.” Steeped in the ideals of the Protestant work ethic, he assured whites that blacks were loyal people who believed they would prosper in proportion to their hard work. Agitation for social equality, Washington argued, was but folly, and most blacks realized the privileges that would come from “constant struggle rather than of artificial forcing.”

Washington also eased many whites’ fears about blacks’ desire for social integration by stating that both races could “be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” Washington’s speech also called for whites to take responsibility for improving social and economic relations between the races. Praising the South for some of the opportunities it had given blacks since emancipation, Washington asked whites to trust blacks and provide them with opportunities so that both races could advance in industry and agriculture.

Cast down your bucket where you are

This phrase surfaced numerous times throughout Washington’s speech. Generally, the phrase had different meanings for whites and blacks. For whites, Washington seemed to be challenging their common misperceptions of black labor. The North had been experiencing labor troubles in the early 1890s (Homestead Strike, Pullman Strike, etc.) and Washington sought to capitalize on these issues by offering Southern black labor as an alternative, especially since his Tuskegee Institute was in the business of training such workers. For blacks, however, the “Bucket motif” represented a call to personal uplift and diligence, as the South needed them to rebuild following the Civil War.

Aftermath

The speech was greeted by thunderous applause and a standing ovation. Clark Howell, editor of the Atlanta Constitution, moved forward to the speaker’s platform and proclaimed the speech to be “the beginning of a moral revolution in America.” Washington’s words, telegraphed to every major newspaper in the country, were greeted enthusiastically by whites—both northern and southern—and by most African American leaders.

The speech also cemented Washington’s status as the most influential black leader and educator in the United States between 1895 and 1915. Due partially to his conditional acceptance of racial subordination, Washington served as an advisor to U.S. presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, both men with deep racial biases. Washington was able to help Roosevelt and Taft select black candidates for nominal, traditionally black political positions. Washington also advised rich industrialists on how best to direct their money to support black education in the South and, in so doing, largely controlled the funding of most black southern schools.

As time went on he gained critics of the approach.

Washington had his critics, none more aggressive than another leading black educator and scholar of his day—W. E. B. Du Bois. Du Bois, a native of Great Barrington, Massachusetts, was educated at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee; Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts; and the University of Berlin in Germany. In 1897 he accepted an appointment to the faculty of Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University) and moved to Atlanta. Although Du Bois recognized Washington’s speech as important, he soon came to see Washington’s ideas of gradualism for civil rights as acquiescence to many southerners who wanted to maintain the inferior status of blacks. In Du Bois’s view, “Mr. Washington represents in Negro thought the old attitude of adjustment and submission. . . . [His] programme practically accepts the alleged inferiority of the Negro races.”

Du Bois’s upbringing in New England and his exposure to liberal democratic views elicited a very different response to the Negro problem. That different response crystallized with the publication of Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk in 1903. Du Bois believed that blacks should launch legal and scholarly attacks on racism and discrimination without hesitation, and he called for education of the most talented blacks to lead this struggle. The “talented tenth,” he believed, should represent the antithesis of gradualism and should seek to free blacks in the present. The Souls of Black Folk rallied opposition to Washington in black intellectual circles.

Leaders of the black community were polarized into two camps: the “conservative” supporters of Washington’s accomodationism, and the “radical” critics of Washington. Du Bois, harnessing radicals’ unhappiness with Washington, founded the Niagara Movement in 1905, which advocated for civil rights for black people and led to the creation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

The Atlanta Compromise represented Booker T. Washington’s strategy for addressing the Negro problem and has long served as the basis for contrasting Washington’s views with those of Du Bois. Even today, scholars and educators debate the utility of Washington’s educational ideas. Most agree that to understand Washington’s speech, it is necessary to place his thinking within its historical context, at a time when African Americans were struggling to transition economically from the legacy of slavery.