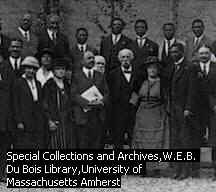

The 1st Pan African Conference

At the first Pan African Conference a permanent organization was formed and the following officers were elected to serve for two years: Bishop A. Walters, New Jersey, President; Rev. Henry B. Brown, London, Vice-President; Prof. W. E. B. DuBois, Georgia, Vice-President for America. Mr. H. Sylvester Williams, General Secretary; T. J. Calloway, Secretary for America; Dr. R. J. Colenzo, Treasurer.

At the first Pan African Conference a permanent organization was formed and the following officers were elected to serve for two years: Bishop A. Walters, New Jersey, President; Rev. Henry B. Brown, London, Vice-President; Prof. W. E. B. DuBois, Georgia, Vice-President for America. Mr. H. Sylvester Williams, General Secretary; T. J. Calloway, Secretary for America; Dr. R. J. Colenzo, Treasurer.

Executive Committee: S. Coleridge Taylor, John R. Archer, J. F. Loudin, Henry T. Downing, Mrs. J. Cobden Unwin, Miss Annie J. Cooper.

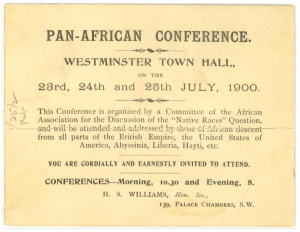

The Conference

When the First Pan-African Conference opened on Monday, 23 July 1900, in London’s Westminster Hall, Bishop Alexander Walters in his opening address, “The Trials and Tribulations of the Coloured Race in America”, noted that “for the first time in history black people had gathered from all parts of the globe to discuss and improve the condition of their race, to assert their rights and organize so that they might take an equal place among nations.” The Bishop of London, Mandell Creighton, gave a speech of welcome “referring to ‘the benefits of self-government’ which Britain must confer on ‘other races … as soon as possible’.”

Speakers over the three days addressed a variety of aspects of racial discrimination. Among the papers delivered were: “Conditions Favouring a High Standard of African Humanity” (C. W. French of St. Kitts), “The Preservation of Racial Equality” (Anna H. Jones, from Kansas), “The Necessary Concord to be Established between Native Races and European Colonists” (Benito Sylvain, Haitian aide-de-camp to the Ethiopian emperor), “The Negro Problem in America” (Anna J. Cooper, from Washington), “The Progress of our People” (John E. Quinlan of St. Lucia) and “Africa, the Sphinx of History, in the Light of Unsolved Problems” (D. E. Tobias from the USA).

Other topics included Richard Phipps’ complaint of discrimination against black people in the Trinidadian civil service and an attack by William Meyer, a medical student at Edinburgh University, on pseudo-scientific racism. Discussions followed the presentation of the papers, and on the last day George James Christian, a law student from Dominica, led a discussion on the subject “Organized Plunder and Human Progress Have Made Our Race Their Battlefield”, saying that in the past “Africans had been kidnapped from their land, and in South Africa and Rhodesia slavery was being revived in the form of forced labour.”

The conference culminated in the conversion of the African Association (formed by Sylvester Williams in 1897) into the Pan-African Association, and the implementation of a unanimously adopted “Address to the Nations of the World”, sent to various heads of state where people of African descent were living and suffering oppression. The address implored the United States and the imperial European nations to “acknowledge and protect the rights of people of African descent” and to respect the integrity and independence of “the free Negro States of Abyssinia, Liberia, Haiti, etc.”

Signed by Walters (President of the Pan-African Association), the Canadian Rev. Henry B. Brown (Vice-President), Williams (General Secretary) and Du Bois (Chairman of the Committee on the Address), the document contained the phrase “The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the colour-line“, which Du Bois would use three years later in the “Forethought” of his book The Souls of Black Folk.

In September, the delegates petitioned Queen Victoria through the British government to look into the treatment of Africans in South Africa and Rhodesia, including specified acts of injustice perpetrated by whites there, namely:

- The degrading and illegal compound system of labour in vogue in Kimberley and Rhodesia.

- The so-called indenture, i.e., legalized bondage of African men and women and children to white colonists.

- The system of compulsory labour in public works.

- The “pass” or docket system used for people of colour.

- Local by-laws tending to segregate and degrade Africans such as the curfew; the denial to Africans of the use of footpaths; and the use of separate public conveyances.

- Difficulties in acquiring real property.

- Difficulties in obtaining the franchise.

The response eventually received by Sylvester-Williams on 17 January 1901 stated:

Sir. I am directed by Mr Secretary Chamberlain to state that he has received the Queen’s commands to inform you that the Memorial of the Pan-African Conference requesting the situation of the native races in South Africa, has been laid before Her Majesty, and that she was graciously pleased to command him to return an answer to it on behalf of her government.

2. Mr. Chamberlain accordingly desires to assure the members of the Pan-African Conference that, it settling the lines on which the administration of the conquered territories is to be conducted, Her Majesty’s Government will not overlook the interests and welfare of the native races.

Days later, Victoria responded more personally, instructing her private secretary, Arthur Bigge, to write, which he did on 21 January – the day before the Queen died. Although the specific injustices in South Africa continued for some time, the conference brought them to the attention of the world

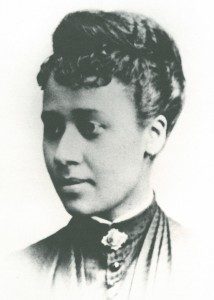

African American Feminism was born at this conference by Executive Committee member Anna J. Cooper.

African American Feminism was born at this conference by Executive Committee member Anna J. Cooper.

Miss Cooper wrote, A Voice From the South, what many consider one of the original texts foretelling the black feminist movement, this collection of essays, first published in 1892.

Pages 24 and 25 of the 2016 United States passport contain the following quotation: “The cause of freedom is not the cause of a race or a sect, a party or a class – it is the cause of humankind, the very birthright of humanity.” – Anna Julia Cooper

She was present at the first Pan-African Conference in London in 1900, elected a Executive Committee Member and delivered a paper entitled “The Negro Problem in America”,

A nation’s greatness is not dependent upon the things it make and uses. Things without thots [ sic] are mere vulgarities. America can boast her expanse of territory , her gilded domes, her paving stones of silver dollars; but the question of deepest moment in this nation today is its men and its women , the elevation at which it receives its “vision into the firmament of eternal truth.

— Anna J. Cooper, The Ethics of the Negro Question, September 5, 1902

Notes on the conference by Bishop Alexander Walters, b. 1858 in his book My Life and Work: Electronic Edition. starting page 253

THE PAN-AFRICAN CONFERENCE

IT was the fertile brain of Mr. H. Sylvester Williams, a young barrister of London, England, that conceived the idea of a convocation of Negro representatives from all parts of the world. He presented his plan by letter to a number of distinguished Negroes in different countries, and after a favorable reply from them, he issued the call in the early part of last year (1900) for the Pan-African Conference, which was held in London, July 23-25.

The objects of the meeting were: First, to bring into closer touch with each other the peoples of African descent throughout the world; second, to inaugurate plans to bring about a more friendly relation between the Caucasian and African races; third, to start a movement looking forward to the securing to all African races living in civilized countries their full rights and to promote their business interests.

The meetings were held in Westminster Town Hall, which is near the House of Parliament. There were present the following representatives: Rt. Rev. A. Walters, D.D., New Jersey; M. Benito Sylvain, Aide-de-Camp to Emperor Menelik,

Page 254

Abyssinia; Hon. F. S. R. Johnson, ex-Attorney-General, Republic of Liberia; C. W. French, Esq., St. Kitts, B. W. I.; Prof. W. E. B. DuBois, Georgia; G. W. Dove, Esq., Councillor, Freetown, Sierra Leone, W. A.; A. F. Ribero, Esq., Barrister-at-Law, Gold Coast, W. A.; Dr. R. A. K. Savage, M.B., Ch.B., Delegate from Afro-West Indian Literary Society, Edinburgh, Scotland; Mr. S. Coleridge Taylor, A.R.C.M., London, Eng.; A. Pulcherie Pierre, Esq., Trinidad, B. W. I.; H. Sylvester Williams, Esq., Barrister-at-Law, London, Eng.; Chaplain B. W. Arnett, Illinois; John E. Quinlan, Esq., Land Surveyor, St. Lucia, B. W. I.; R. E. Phipps, Esq., Barrister-at-Law, Trinidad, B. W. I.; Mr. Meyer, Delegate Afro-West Indian Literary Society, Edinburgh, Scotland; Rev. Henry Smith, London, Eng.; Prof. J. L. Love, Washington, D. C.; G. L. Christian, Esq., Dominica, B. W. I.; J. Buckle, Esq., F.R.G.S., F.C.I.E., London, Eng.; Hon. Henry F. Downing, U. S. A. ex-Consul, Loando, W. A.; T. J. Calloway, Washington, D. C.; Rev. Henry B. Brown, Lower Canada; Dr. John Alcinder, M.B., L.R.C.P.; Counsellor Chas. P. Lee, New York; Mr. J. F. Loudin, Director Fisk Jubilee Singers, London, Eng.; A. R. Hamilton, Esq., Jamaica, B. W. I.; Rev. H. Mason Joseph, M.A., Antigua, B. W. I.; Miss Anna H. Jones, M.A., Missouri; Miss Barrier, Washington, D. C.; Mrs. J. F. Loudin, London, Eng.; Mrs. Annie J. Cooper, Washington D. C.; Miss Ada Harris, Indiana.

The writer was chosen to preside at the meetings.

Prof. J. L. Love, of Washington, D. C., was elected secretary, and Prof. W. E. B. DuBois, of Georgia, was made chairman of the committee on address to the nations of the world.

The address of welcome was delivered by the late Dr. Creighton, who was Lord Bishop of London at that time. He said he was glad to meet the delegates and to welcome them to the City of London. He assured them that they had the sympathy of the fair-minded throughout the realm. He expressed a hope that the conference would be a precursor of many similar ones. Continuing, he said he was quite confident the great problems with which they were concerned would not be settled in a hurry, but still the movement to be inaugurated that day for the first time in the history of the world, no matter in however humble a way, was sure to go on growing until it brought a mass of public opinion to bear upon the questions raised. These would be of the most vital description, dealing with the future of the world, of which he was not then inclined to speak. For the first time in human experience the entire world had been really discovered, and a sense of human brotherhood had become a very real thing, and, magnificent as were the ideals it created, practical difficulties had to be dealt with. The conference would materially assist towards the accomplishment of this object if the delegates would place on record their experience of the views and aims of the colonial races. England generally recognized the weighty responsibilities

Providence had placed upon her, and her statesmen were constantly considering how to most adequately discharge them, and any help that conference could give them would be most gladly welcomed.

Responses to the most cordial and eloquent address of the Bishop were made by Hon. F. S. R. Johnson, of Liberia, and the presiding officer. During the session excellent papers were read by M. Benito Sylvain, C. W. French, Miss Anna Jones, Mrs. Annie J. Cooper, Rev. H. Mason Joseph, Francis Ware, Esq.; Rev. Henry Smith and others. The papers and addresses elicited great praise from the London daily press.

A Memorial, setting forth the following acts of injustice directed against Her Majesty’s subjects in South Africa and other parts of her dominions, was prepared and sent to Queen Victoria:

1. The degrading and illegal compound system of native labor in vogue in Kimberley and Rhodesia. 2. The so-called indenture, i.e., legalized bondage of native men and women and children to white colonists. 3. The system of compulsory labor on public works. 4. The “pass” or docket system used for people of color. 5. Local by-laws tending to segregate and degrade the natives, such as the curfew; the denial to the natives of the use of the footpaths; and the use of separate public conveyances. 6. Difficulties in acquiring real property. 7. Difficulties in obtaining the franchise.

The following is the reply received from Her Majesty by our secretary, Mr. H. Sylvester Williams:

Page 257

16th January, 1901.

Sir: I am directed by Mr. Secretary Chamberlain to state that he has received the Queen’s commands to inform you that the Memorial of the Pan-African Conference respecting the situation of the native races in South Africa has been laid before Her Majesty, and that she was graciously pleased to command him to return an answer to it on behalf of her Government.

2. Mr. Chamberlain accordingly desires to assure the members of the Pan-African Conference that, in settling the lines on which the administration of the conquered territories is to be conducted, Her Majesty’s Government will not overlook the interests and welfare of the native races.

3. A copy of the Memorial has been communicated to the High Commissioner for South Africa.

I am, sir, your obedient servant,

H. BERTRAM COX.

H. S. Williams, Esq.

On Monday, the 23d of July (1900), the conference was invited to a five o’clock tea given by the Reform Cobden Club of London in honor of the delegates, at its headquarters in the St. Ermin Hotel, one of the most elegant in the city. Several members of Parliament and other notables were present. A splendid repast was served, and for two hours the delegates were delightfully entertained by the members and friends of the club.

At 5 o’clock on Tuesday a tea was given in our honor by the late Dr. Creighton, Lord Bishop of London, at his stately palace at Fulham, which has been occupied by the Bishops of London since the fifteenth century. On our arrival at the palace we found his Lordship and one or two other Bishops, with their wives and daughters, waiting to greet us. After a magnificent repast had been served we were conducted through the extensive grounds which surround the palace. Prof. DuBois, M. Benito Sylvain, Messrs. Downing and Calloway, Miss Jones and others moved about the palace and grounds with an ease and elegance that was surprising; one would have thought they were “to the manor born.” We found the Lord Bishop not only a brilliant scholar and profound thinker, but an affable Christian gentleman. I am sure our visit to the palace will be long remembered by the delegates as one of the most pleasant in their history.

Page 262

Through the kindness of Mr. Clark, a member of Parliament, we were invited to tea on Wednesday, at 5 o’clock, on the Terrace of Parliament. After the tea the male members of our party were admitted to the House of Commons, which is considered quite an honor; indeed, the visit to the House of Parliament and tea on the Terrace was the crowning honor of the series. Great credit is due our genial secretary, Mr. H. Sylvester Williams, for these social functions.

Miss Catherine Impey, of London, said she was glad to come in contact with the class of Negroes that composed the Pan-African Conference, and wished that the best and most cultured would visit England and meet her citizens of noble birth, that the adverse opinion which had been created against them in some quarters of late by their enemies might be changed.

I am glad that so many of our ministers, educators and other members of the professional classes are making annual visits to Europe. Such visits are helpful to our cause. The Pan-African Association and the Afro-American Council, if efficiently officered and wisely managed, can do much for the amelioration of the condition of persons of African descent throughout the world, provided that they are supported in their work by the better classes of our people. Without such co-operation they are sure to fail.

If political parties, capital and labor see the need of organization, surely, as a race, oppressed and moneyless, we ought to see the necessity

Page 263

of a great National and International organization. It is the aim and hope of the Pan-African Association, which is neither circumscribed by religious, social or political tests as a condition to the membership therein, to incorporate in its membership the ablest and most aggressive representatives of African descent in all lands.

We are not unmindful of the fact that it will require considerable time and labor to accomplish our object, but we have resolved to do all in our power to bring about the desired results.

The numerous letters I have received from different parts of the world commending the work of the Pan-African Association and the National Afro-American Council, the many local organizations which are being formed in various countries for the betterment of persons of African descent, the host of newspaper and magazine articles published by colored men in defense of the race, and the encouragement that is being given to our educational and financial development, are all evidences of a great awakening on the part of the Negroes to their own interests, and an abundant proof that the time is ripe for the inauguration of a great international as well as national organization.

Since these organizations have for their objects the encouragement of a feeling of unity and of friendly intercourse among all persons of African descent, the securing to them their civil and political rights, and the fostering of business enterprises among us, their growth in order to be

Page 264

permanent must necessarily be slow. But since great bodies move slowly, we need not be discouraged. As a race we have learned to laugh at opposition and to bravely overcome difficulties. Let us not be deterred by them in the future, but march steadily forward to the goal.

History

On 24 September 1897, Henry Sylvester Williams had been instrumental in founding the African Association (not to be confused with the Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa), in response to the European partition of Africa that followed the 1884-5 Congress of Berlin.

The formation of the association marked an early stage in the development of the anti-colonialist movement, and was established to encourage the unity of Africans and people of African descent, particularly in territories of the then British empire, concerning itself with injustices in Britain’s African and Caribbean colonies. In March 1898 the association issued a circular calling for a pan-African conference. Booker T. Washington, who had been travelling in the UK in the summer of 1899, wrote in a letter to African-American newspapers:

“In connection with the assembling of so many Negroes in London from different parts of the world, a very important movement has just been put upon foot. It is known as the Pan-African Conference. Representatives from Africa, the West Indian Islands and other parts of the world, asked me to meet them a few days ago with a view to making a preliminary program for this conference, and we had a most interesting meeting. It is surprising to see the strong intellectual mould which many of these Africans and West indians possess. The object and character of the Pan-African Conference is best told in the words of the resolution, which was adopted at the meeting referred to, viz: ‘In view of the widespread ignorance which is prevalent in England about the treatment of native races under European and American rule, the African Association, which consists of members of the race resident in England and which has been in existence for nearly two years, have resolved during the Paris Exposition of 1900 (which many representatives of the race may be visiting) to hold a conference in London in the month of May of the said year, in order to take steps to influence public opinion on existing proceedings and conditions affecting the welfare of the natives in various parts of Africa, the West Indies and the United States.’ The resolution is signed by Mr H. Mason Joseph, President, and Mr H. Sylvester Williams as Honourable Secretary. The Honourable Secretary will be pleased to hear from representative natives who are desirous of attending at an early date. He may be addressed, Common Room, Grey’s (sic) Inn, London, W.C.