The 1830 – 1890’s Negro Convention Movement

The Colored Conventions Movement or known today as organizational effort known as the Negro Convention Movement was a series of national, regional, and state conventions held irregularly during the decades preceding and following the American Civil War.

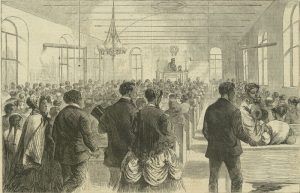

Above – February 6, 1869 illustration from Harper’s Weekly: The National Colored Convention in Session at Washington, D.C.–Sketched by Theo. R. Davis

In first known one was in September 1830, black representatives from seven states convened in Philadelphia at the Bethel AME church for the first Negro Convention. A civic meeting, it was the first on such a scale organized by African-American leaders. Allen presided over the meeting, which addressed both regional and national topics. The convention occurred after the 1826 and 1829 riots in Cincinnati, when whites had attacked blacks and destroyed their businesses. After the 1829 rioting, 1200 blacks had left the city to go to Canada. As a result, the Negro Convention addressed organizing aid to such settlements in Canada, among other issues.

Before the American Civil War the delegates who attended these conventions consisted of both free and fugitive African American community and religious leaders, businessmen, politicians, writers, publishers, and abolitionists. The minutes from these conventions show that Antebellum African-Americans sought justice beyond the emancipation of their enslaved countrymen: they also organized to discuss issues concerning labor, healthcare, temperance and educational equality.

The convention movement took place during critical decades which witnessed devastating race riots and the growing popularity of the American Colonization Society; the Fugitive Slave Law  and the proliferation of derogatory representations of Blacks; the Civil War and Reconstruction; and the rise of repeated Black disenfranchisement in legal, labor and educational spheres in the late nineteenth century. Speakers at conventions responded to these issues by calling for community-based action that gathered funds, established schools and literary societies, and urged the necessity of hard work in what would become a decades-long campaign for civil and human rights. The convention minutes collected here illustrate the immense struggles and the profound courage of those who made it a point to organize and stand for what was rightly theirs.

When delegates to the 1865 “State Convention of the Colored People of South Carolina” met on Charleston’s Calhoun Street, they gathered “for the purpose of deliberating upon the plans best calculated to advance the interests of our people [and] to devise means for our mutual protection.” Convening in the heart of the Confederacy less than a year after its fall, among their first orders of business was a motion to appoint “doorkeepers” and a Sergeant of Arms. This six-day meeting was held in Zion Church, which stood “nearly opposite” to what was slated to become—that very month—Mother Emanuel AME Church’s first new building since it was forced underground after the famous revolt planned by one of its founders, Denmark Vesey. “Resolved,” they declared, “that we will insist upon the establishment of good schools for our children throughout the state.”

But though it begins in 1830 at Philadelphia’s Mother Bethel AME Church, it swells rather than stops in 1865. Indeed, in the churches and halls in which they met, attendees fleshed out issues that reached well beyond the thematic and temporal boundaries of slavery; they insisted on their claim to dignity and to full human and citizenship rights. They demanded that their children be free not only to survive the violence meted out by the state and its recognized citizens—but also to thrive and prosper.

The directed post-war conventions culminated with the 1869 National Convention of Colored Men in Washington, D.C. The convention delegates wrote a letter congratulating General Ulysses S. Grant for being elected President of the United States, to which Grant responded, “I thank the Convention, of which you are the representative, for the confidence they have expressed, and I hope sincerely that the colored people of the Nation may receive every protection which the laws give to them. They shall have my efforts to secure such protection.”

As national, state, and local colored conventions began to decline, other national organizations popped up. In response to a denial of African American admittance to the National Labor Union, community leaders and others formed the Colored National Labor Union in December 1869. Former Colored Convention delegates Isaac Myers and Frederick Douglass were instrumental in organizing the CNLU.

The last known colored convention took place in Indianapolis in 1887.

Far from being centuries removed from the pressing concerns of today’s Black organizers, parents, community leaders, and laborers, the scenes and scenarios discussed at these conventions speak directly to the value of Black lives and to the continuously necessary assertion that they do, in fact, matter, then as now.

Select a convention to learn more information, to view minutes in a document viewer, or to download minutes in pdf format.

1830s | 1840s | 1850s | 1860s | 1870s | 1880s | 1890s

Thank you University of Delaware Library Institutional Repository (UDSpace) for providing space for and preserving this collection.

This section is possible becuase of P. Gabrielle Foreman who is the Ned B. Allen Professor of English and Professor of History and Black American Studies at the University of Delaware. She has published extensively on issues of race, slavery and reform in the nineteenth century with a focus on the past’s continuing hold on the world we inhabit today. In the 1990s, she was part of a three person interdisciplinary that fully integrated digital technologies into first-year required courses at liberal arts colleges for the first time. Foreman is the founding faculty director of the Colored Conventions Project, which since 2012 has made digitally available six decades of Black political organizing that overlapped with and was obscured by the abolitionist movement. The project has involved over 1000 students across the country in undergraduate research through its curriculum adopted by the Project’s national teaching partners while launching a transcription project recognized alongside those by the British Library and the Massachusetts Historical Society.