FAU Cincinnati Chapter

This bank will have right of first refusal –

This bank will have right of first refusal –

Nineteenth-Century Cincinnati was northern in its geography, southern in its economy and politics, and western in its commercial aspirations. While those identities presented a crossroad of opportunity for native whites and immigrants, African Americans endured economic repression and a denial of civil rights, compounded by extreme and frequent mob violence. No other northern city rivaled Cincinnati’s vicious mob spirit. Frontiers of Freedom follows the black community as it moved from alienation and vulnerability in the 1820s toward collective consciousness and, eventually, political self-respect and self-determination. This was a community that at times supported all-black communities, armed self-defense, and separate, but independent, black schools. Black Cincinnati’s strategies to gain equality and citizenship were as dynamic as they were effective. When the black community united in armed defense of its homes and property during an 1841 mob attack, it demonstrated that it was no longer willing to be exiled from the city as it had been in 1829.

Nineteenth-Century Cincinnati was northern in its geography, southern in its economy and politics, and western in its commercial aspirations. While those identities presented a crossroad of opportunity for native whites and immigrants, African Americans endured economic repression and a denial of civil rights, compounded by extreme and frequent mob violence. No other northern city rivaled Cincinnati’s vicious mob spirit. Frontiers of Freedom follows the black community as it moved from alienation and vulnerability in the 1820s toward collective consciousness and, eventually, political self-respect and self-determination. This was a community that at times supported all-black communities, armed self-defense, and separate, but independent, black schools. Black Cincinnati’s strategies to gain equality and citizenship were as dynamic as they were effective. When the black community united in armed defense of its homes and property during an 1841 mob attack, it demonstrated that it was no longer willing to be exiled from the city as it had been in 1829.

The list of Most Segregated Cities in America according to 2010 US Census data are as follows: 10) Los Angeles, 9) Philadelphia, 8) Cincinnati, 7) St. Louis, 6) Buffalo, 5) Cleveland, 4) Detroit, 3) Chicago, 2) New York City, and 1) Milwaukee. Interestingly enough, not a single Southern city broke the Top 10.

Racial History

1829: After watching the free African American population of Cincinnati quadruple in the course of a decade, pro-slavery whites in the city enforce an archaic black law that demands all blacks pay a $500 bond ($11,000 in 2013 dollars) within 30 days in order to be a legal Ohio citizen. When the city’s black population can’t pay, mobs of whites attacked black neighborhoods, demolishing houses and beating their former residents. 50 to 70 percent of the city’s black population would emigrate within the week.

1836: The establishment of an anti-slavery newspaper, The Philanthropist, by noted Southern abolitionist James G. Birney led to a series of small riots that broke out sporadically over the spring and summer of 1836. Encouraged by the city’s pro-slavery mayor and Jacksonian political establishment, numerous black residences and shops were burned to the ground while their occupants were savagely beaten and the offices of The Philanthropist were destroyed twice by mobs in an attempt to stop the publication’s continued existence.

1841: In what was arguably the largest pre-Civil War race riot in American history, a large white mob attacked a black neighborhood near 6th Street and Broadway, beating an undisclosed number of black Cincinnatians to death and razing some black owned businesses. The black community responded with an armed resistance, pushing the rioters back for several hours until the white mob got their hands on a six-pound cannon and began firing it into the neighborhood. The next day, armed guards penned 300 black men into the square at intersection of 6th & Broadway before hauling them off to jail while the city descended into anarchy. By the time the mob had dispersed, the offices of The Philanthropist had been destroyed for a 3rd time in 5 years and much of the black community’s private property had been destroyed.

1843: Mob action was taken after an enslaved 9-year old girl managed to run away from her Louisiana “master” upon reaching Cincinnati, having been told by her mother that she could gain her freedom if she quickly sought protection. The riot itself was mostly bluster, but an abolitionist confectioner’s shop was damaged and surrounded by an angry group of slavery supporters for several hours. While relatively uneventful, the event is noteworthy if only for the accounts we have of it from the diary of a local banker, who remarks on the widespread societal acceptance of such racially motivated vigilantism, noting that, “the mob of Cincinnati must have their annual festival – their Carnival, just as at stated periods, the ancient Romans enjoyed the Saturnalia, and our city dig-nitaries [sic] must run no risk of forfeiting their ‘sweet voices’ at the next charter election by any unceremonious interference with their ‘gentle violence’ – their practical demonstrations of sovereignty.”

1853: as his guest during what was the first diplomatic visit from a Papal emissary in the United States. Upon Bedini’s arrival, several hundred German residents marched towards the Archbishop’s residence and clashed with a large detail of policemen that were assigned to guard the house. All in all, 2 people were killed during the riot, and a further dozen wounded.

1855: Tensions in Cincinnati between Nativists and German immigrants came to a head during the April elections of 1855. With Nativists putting their support behind the anti-immigrant Know Nothing party and newly arrived Germans backing the Democratic party, the election quickly devolved into mob rule that spread throughout the city. The Know-Nothings, who imported over 300 rogue Kentuckians to help them “watch the polls,” went about heavily German wards, trying to destroy as many ballot boxes as they could while the Germans themselves set to building up a resistance, eventually erecting makeshift barricades on all of the bridges connecting their neighborhood to the center of the city. After 3 days of prolonged fighting and an unknown number of casualties, the conflict finally subsided and would serve as the last hurrah for the Know-Nothings in the Queen City.

1862: Amidst the turmoil and racial unrest at the beginning of The Civil War,an argument between two groups of black and Irish stevedores turned violent and ushered in a week of intense rioting throughout the city. Most of the destruction was contained to the city’s largest black neighborhood, the pejoratively named “Bucktown”, and after a week of escalating vandalism and assault virtually the entire black population of the city had dispersed to the country to escape danger.

1884: With Cincinnati seeing increased crime rates and a perceived paucity of capital punishment, the city erupted into one of the largest riots in American historyafter a German immigrant named William Berner was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment for the lesser charge of manslaughter in the murder of his employer, William Kirk, despite the fact that Berner had already confessed to the murder itself. Outraged at the injustice, thousands packed into the city’s Music Hall to make their displeasure known. Predictably, order was quickly lost and a vast mob poured out onto the streets, looking for vengeance. Over the course of three days, the more than 10,000 rioters set fire to the city jail and to the courthouse, fighting with a Ohio National Guardsmen in battles so pitched that they were actually compared to the assault on the Bastille. When the rioting finally died down, 56 men had been killed and over 300 more injured. A racially tinged side note is that Berner’s accomplice, a biracial man named Joe Palmer, was tried separately for the murder and was later hanged.

1967: The longest riot free period in the city’s history ended during the Long Hot Summer of 1967, as several black neighborhoods erupted in protestation and violence in response to an oppressive socioeconomic climate that hadn’t changed much during the 20th century. As with many of the 159 riots that took place that year, the unrest in Cincinnati began when a black man was unjustly arrested, in this case for protesting a guilty verdict that had been handed down against his cousin, who was convicted of raping and murdering six white women despite a complete lack of physical evidence. The rioting, which was finally quelled by an influx of National Guardsmen after raging for four days, resulted in one death, over 400 arrests and property damage in excess of $2 million.

1968: After the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr, the already strained racial tensions in the city snapped for the second time in under a year.As demonstrations were going on to memorialize Dr. King and condemn white society for its role in his death, a local black jeweler accidentally shot and killed his wife while protecting his shop from an attempted robbery. By the time the story began circulating in the black community, the accidental shooting had erroneously transformed into the murder of a black woman by a white police officer. Rioting ensued shortly thereafter and continued for several days. When the dust had settled, two people were dead, hundreds more were arrested and about $3 million in property had been destroyed.

2001: The police shooting of unarmed 19-year old Timothy Thomas precipitates the largest race riot in 21st century American history.

In the early morning hours of April 7th, 2001, a familiar scene was being played out in the Over-The-Rhine neighborhood of Cincinnati. A 19-year old black man, Timothy Thomas, was walking past a nightclub called “The Warehouse” when he was spotted by two off-duty Cincinnati Police officers who recognized him as someone who had open warrants out against him. Almost immediately after the two officers approached him, Thomas ran off. The two off-duty cops gave chase to Thomas and they were soon joined by several on-duty officers, including Officer Stephen Roach, who chased Thomas into an back alley. Within moments of his entering the alley, Officer Roach fired his weapon at Thomas a single time as the young man was running away from him. The bullet fired by Roach pierced Thomas’s heart, a wound which would prove fatal less than an hour later. Roach initially claimed in an official statement that he fired at Thomas because he thought he saw the young man reaching into his waistband for a gun, but would later admit that the shooting happened because he had been chasing the 19-year old with his finger on the trigger when Thomas startled him by coming around a corner, causing him to inadvertently fire a shot off.

The off-duty cops who initiated this tragic sequence of events did so because Timothy Thomas had a total of 14 outstanding arrest warrants against him, a backlog that sounds rather impressive until you find out that 8 of those 14 warrants were for driving without a license and another 4 were for driving without a seatbelt. The other two outstanding warrants on him stemmed from charges for “obstructing official business”or, in layman’s terms, running away from the cops because they wanted to arrest him for prior traffic violations. Put simply, Timothy Thomas was about as much of a criminal as someone who habitually jaywalks or litters. There are no drug charges on his record. He was never arrested for shoplifting or domestic violence charges. Hell, for the most part he wasn’t even a bad driver. Thomas was never pulled over for speeding or running a red light or making a rolling stop at a stop sign. The two main traffic offenses that led to Thomas’s outstanding warrants, driving without a license and without wearing a seatbelt, are not moving violations. The only time that a law enforcement officer can legally charge someone with either of those violations is after he or she has already pulled the driver over for a separate incident, the reason for this being that no police officers, no matter how good they are, can tell if a car is being driven by a licensed driver by watching it drive past their cruiser at 35 miles an hour.

The absurd collection of traffic violations accrued by Timothy Thomas over the course of about a year show the extent to which the Cincinnati Police used racial profiling while out on patrol. During a 65 day period of time in the spring of 2000, Thomas was issued a staggering 12 citations by Cincinnati Police officers. On both March 6th and March 10th, he was pulled over twice within a 6 hour period, with only one of the 4 stops being conducted for a moving violation.

Racial History 2016

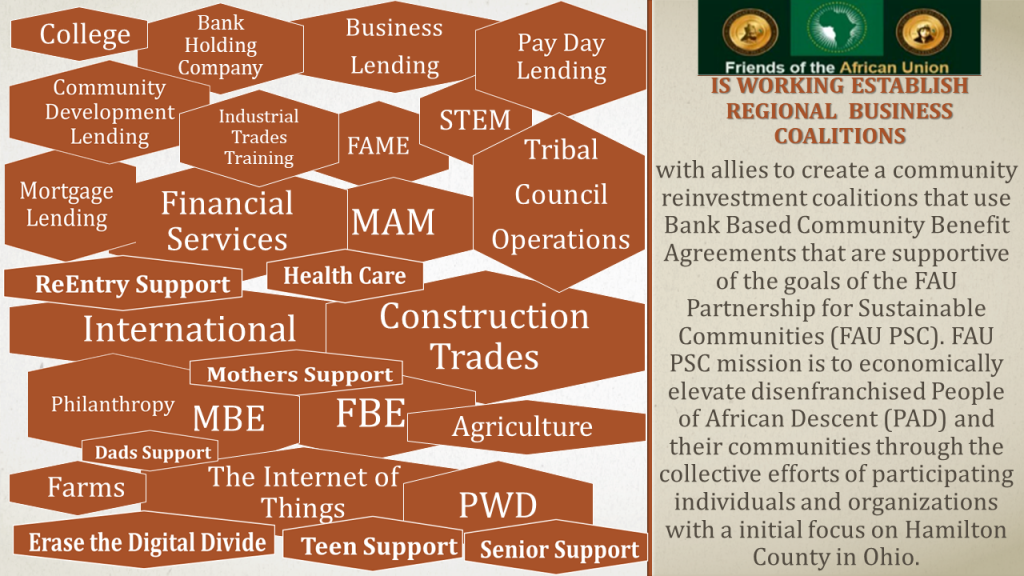

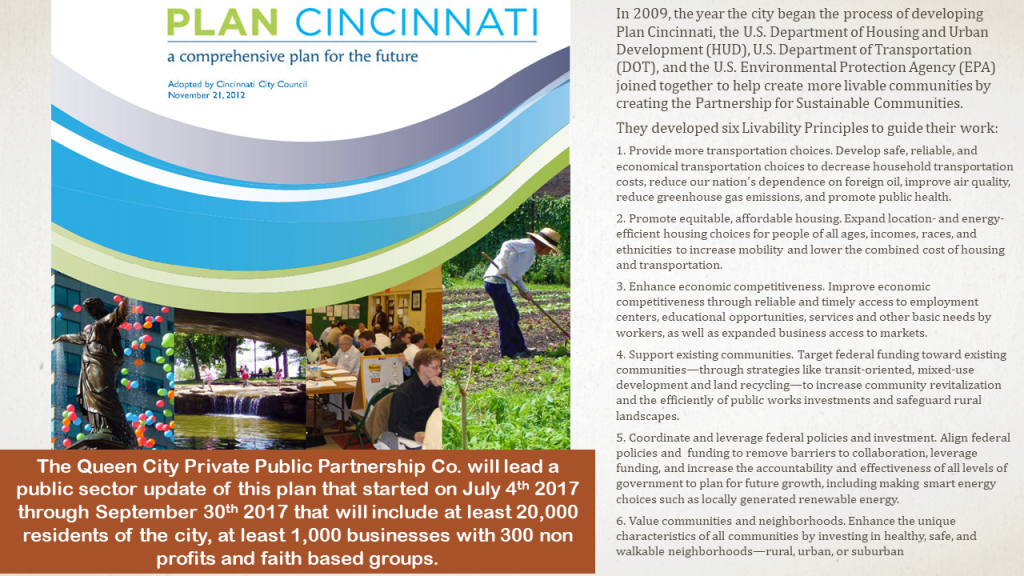

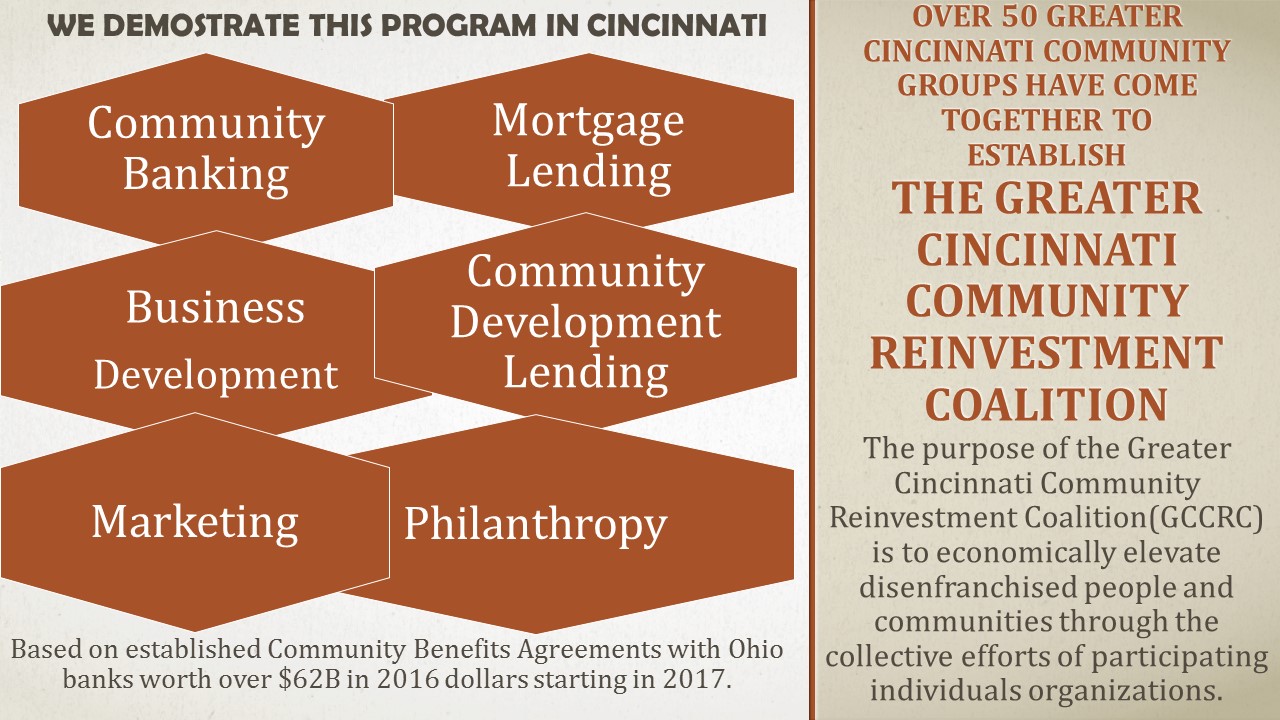

In short, Cincinnati is the poster child for unstable race relations in America; FAU aims to change that by helping create the Greater Cincinnati Community Reinvestment Coalition.

FAU was a founding member Greater Cincinnati Community Reinvestment Coalition.

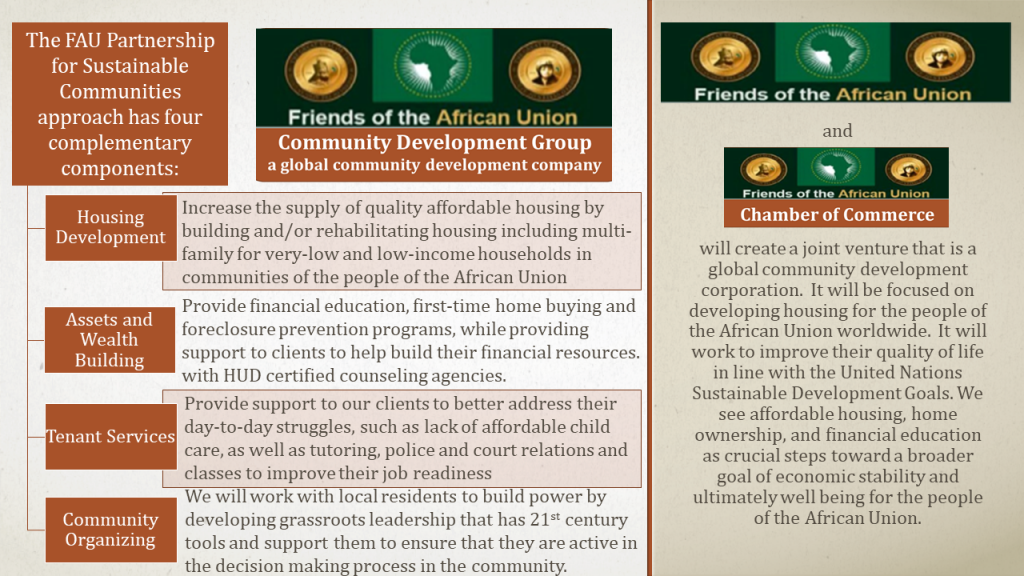

Founding meeting of the Greater Cincinnati Community Reinvestment Coalition which had these goals. We resigned our leadership of the Pay Day Lending Subcommittee based on the fact the leadership rejected our community banking proposal to create a financial technology company to do best practice operations including payday lending as per the decision of the majority member organizations as a result of our videotaped January 2017 meeting of the whole.

The rejected proposal coevrsheet looked like this –

Based on work done by FAU leadership at the Cincinnati Black Agenda

Using our membership in the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC)